The Anatomy of Relict Hominids

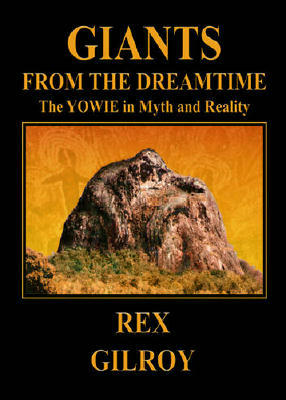

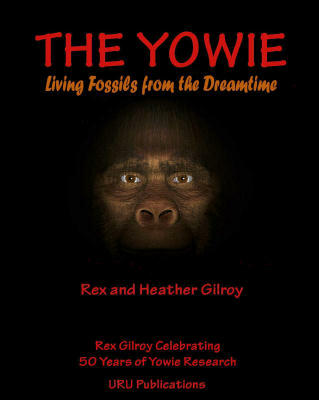

This article is composed of extracts from the 2007 book:

“The Yowie Mystery - Living Fossils From The Dreamtime".Copyright (c) 2007 Rex Gilroy, Uru Publications.

We have, we believe, already established a Homo erectus identify for the traditional tool-making, fire-making “hairy people”, the ‘hairy’ title of course referring to the crude native animal hide garments manufactured and worn by these people. Yet, as we have also shown, the name ‘hairy man’ under whatever variation Australia-wide, referred also to any non-Aboriginal [ie Australoid] race that had preceded them and with whom they shared this continent.

Thus, besides the average modern human height Yowie/Homo erectus, our Aboriginal people recognised ‘little hairy people’ [ie pygmies] of more than one race [even though they often lacked body hair]; a larger ‘hairy man’ of up to 2.8 to 3 metres height and the ‘Rexbeast’ of 3.6 metres height or over! There was also another giant being, of bipedal ape appearance. This later ‘hairy man’ was something else to our early tribespeople, for ‘he’ just did not quite fit into the ‘hominid’ racial slot, which is quite evident from his long haired ape-like appearance.

His features, as described in Aboriginal folklore, compare with those described by many early pioneer settlers accounts and are suggestive of Gigantopithecus blacki, the giant Dryopithecine forest ape of Pleistocene Asia-Java, officially extinct there for the past 100,000 years, but which could have reached Australia across the former land shelf to survive here in Australia into much later, more recent times. And there is also the tantalising prospect that, if not the Asian Gigantopithecus, this race might have evolved here from our ‘unknown’ primate fauna. Whatever the origins of this mysterious giant, the identity of these ape-like enigmas will only be identified not from fossil footprints, but from actual fossil skeletal remains.

The 17 million year old primate hand fossil impression discussed in Chapter Four, displays physical features typical of a species evolved to an arboreal existence. Unfortunately there are no other, better preserved primate remains at present from Australia with which comparisons could be made, although it does possess gibbon-like features.

However, there can be no doubt that it is a primate hand. There was, and still is, a considerable variety in primate hand structure and use. All primates possess hands with moveable fingers, and all evolved from hands like those of the tree shrew, which are little more than elongated paws capable only of essential functions, such as holding onto a tree branch by digging in with claws. By comparison, the hands of the slow loris possess a highly specialised pincer-like grasp, while the tarsier, a jumper, has hands with discs on its finger tips that assist it in holding onto a branch after leaping.

The most arboreal of all the apes are the brachiating gibbons and orang-utans for they posses specialised hands with extraordinarily long, strong fingers that can be fixed into hooks for hanging and swinging. Their thumbs however, are different. That of the orang-utan is short and stumpy and is not an obstruction during brachiation. The thumb of the gibbon is longer, and although sometimes employed in climbing, it can be neatly tucked alongside the palm when its owner is using its other fingers to move in the trees by swinging from branch to branch.

A comparison between the hand of a gibbon and the 17 million year old Miocene fossil hand impression from Mt Victoria, Blue Mountains New South Wales, given its incomplete state is remarkable. Let us now consider the evolutionary differences between the limbs of primates and humans – and remember that WE are also primates, although of a far more evolved example! The more that a primate depends upon a single pair of limbs for locomotion, the longer these limbs will grow and become stronger accordingly. Here we can compare the gibbon with Man. The gibbon moves from tree branch to tree branch by swinging from its arms, which have become elongated to such a degree that their span easily exceeds the total length of its body and legs. On the other hand, Man had developed the ability to walk upright and so had evolved long legs, his arm span unlike that of the gibbon is no greater than his height.

It is a point of interest here, that many obvious hoax sightings claims are beings made by people with no real knowledge of primate anatomy, for many frequently describe human-like ‘Yowies’ as moving upon two legs, covered in excessively long hair [often in a great variety of colours!] with long arms that reach down to their knees. Their imagination extends to the heads of these hairy beasties, which are often described as ‘gorilla-like’ with faces to match. Sometimes the heads are given over-exaggerated pointed sagittal crests. Photograph right: Aboriginal Girl wearing a Kangaroo hide Garment. Photographer Unknown. I will credit anyone who owns this photograph.

The heads are often sunk into the shoulders and to top everything else off, these hairy impossibles possess large eyes that glow in the dark [red being the favoured colour!]. No wonder the Australian media and the scientific community cannot take the Yowie mystery seriously!Our anatomical investigation is principally concerned with the primate suborder Anthropoidea, of the super family Ceboidea, which includes we Homo sapiens as well as extinct types of hominid, the anthropoid apes and the monkeys. As the subordinal name implies, the members of the group are distinguished by their man-like appearance. It would appear that unknown forms of Miocene Anthropoid apes were present in Australia. The anthropoid apes comprise the family Pongidae, and today are represented by four genera, Gorilla, Pan [chimpanzee], Pongo [orang-utan] and Hylobates [gibbon].

The living anthropoid apes resemble the Hominidae structurally more so than do the monkeys. For example the relative size and configuration of the brain, various details of the skull, skeleton and dentition and in the tendency to adopt a semi-erect or orthograde posture. There have been some ridiculous claims made by misinformed ‘Yowie hunters” in recent years, that the objects of their attention have the habit of chewing into the solid wood of gum, wattle and certain other trees, to extract the larvae of large moth species [ie commonly and collectively called Witchetty grubs]. The authors suggest that these people look for cockatoos, well known for this habit, and which possess sharp beaks capable of accomplishing this feat.

The fact is that the muscular/jaw strength of anthropoid apes and hominids is not of sufficient enough power to accomplish such a task, any more than tree-chewing is a regular primate or hominid habit. And then there are the teeth of apes and hominids to consider, for these likewise are not built for this task. Even a study of the teeth/jaw structure of the Giant Java Man, Meganthropus palaeojavanicus, and the 52mm tall lower back premolar tooth of a 3 to 3.66m tall giant Homo erectus, found by the author Rex Gilroy, at Westmead, New South Wales in September 1969 [see Chapter Six] give no indications of the time-wasting exercise of tree-chewing!

Besides, to chew into a tree trunk would require exceptionally tough, sharp front teeth not known even to the fossil apes, giant or otherwise, and no modern-day Yowie/Homo erectus would possess the necessary dental ability to accomplish this task, any more than his fossil Homo erectus forebears. The presence of primate ancestors of Man in the Mt Victoria, Blue Mountains, New South Wales Miocene slate described earlier is part of the above picture. Being anthropoids all are part of the greater picture of pre-Aboriginal Man in Australia. Each of the anthropoid apes resembles Man in one physical characteristic or another.

For example, the gibbons in the formation of the teeth; the orang-utans in the brain-structure; the gorillas in size and the chimpanzees in the sigmoid flexure of the spine. In their general physical structure they all closely resemble human beings; such as in the absence of tails; in their semi-erect posture [ie resting upon finger-tips or knuckles]; in the shape of the vertebral column, sternum and pelvis; in the adaptation of the arms for turning the palm uppermost at will; in the possession of a long vermiform appendix to the short caecum of the intestine; in the size of the cerebral hemispheres and the complexity of their convolutions. They differ in certain respects, as in the proportion of the limbs, in the bony development of the eyebrow ridges and in the opposable great toe which fits the foot to be a climbing and grasping organ.

Homo erectus, like his modern human counterpart, would have differed from these apes in the absence of a thick body coating of hair; in the development of a large lobule to the external ear; in his fully erect posture; in his flattened foot with the non-opposable big toe; in the straight limb-bones; in the wider pelvis; in the perfection of the muscular movements of the arm; in the delicacy of the hand, the smallness of the canine teeth and other dental features; the development of a chin as well as in the small size of his jaws compared to the relatively great size of the cranium.

The foregoing information surely demonstrates that Homo erectus/Yowie is not the hairy monster ‘Yowie’ of the misinformed “Yowie catchers”, emerging instead as an intelligent, tool-making, fire-making race directly ancestral to ourselves. The most distinctive feature of the Primates, is the development of a brain which is large in proportion to the total body weight and which is characterised by a relatively extensive and richly convoluted cerebral cortex. As this book demonstrates, ancestral hominids and later proto-Homo erectus as well as classical Homo erectus lived on this continent when a great land shelf also extended between Australia and mainland Asia.

To begin with, our ancestral hominid forms were all small beings which evolved to greater size with the improvement of their diet. The hominid brain evolved for the same reasons. At present, apart from four large molar teeth of giant Homo erectus origin, the teeth of smaller Homo erectus are extremely rare, although sockets in mineralised jaws suggest they were small. An example are the Australopithecines of Africa who possessed large teeth with thick enamel. In contrast, members of the genus Homo show thinner molar enamel, a dramatic reduction in cheek tooth size, and considerable cranial expansion [Grine 1981; McHenry 1982; S. Ambrose, pers.comm].

In combination, these dental and cranial features, as well as an increase in body size, apparently with no loss of mobility or sociality, strongly imply that early members of the genus Homo made a dramatic breakthrough that enabled them to circumvent the nutritional constraints imposed on body size increases in the apes. Certainly, the rich variety of animal and bird diet available to our Pliocene-Pleistocene hominids played a major role in the development of giant forms of Homo as we shall see ahead in this book. With diet playing a major role in the evolution of our ancestors in Australia and an increase in brain size, the next logical step forward would have been the development of speech.

It was once widely held that language evolved with the development of stone tools and hunting skulls in the course of which groups would need to signal one another, particularly when approaching a mob of game. African Homo erectus was manufacturing primitive stone tools as long ago as 2.4 million years. A number of crude ‘eothlithic’ tools from the 2 million year old Pleistocene beds out on Narrow neck Plateau at Katoomba, New South Wales, where the mineralised, distorted skull-type of a proto-Homo erectus was recovered by the author [see chapter Five] show that tool-making already existed in Australia by that date; while others recovered from sites in the New South Wales central west, far south coast and elsewhere by the Gilroys over the years pre-date the African specimens. Thus, if tool-making by ancestors of Homo erectus in Australia pre-dates this development in Africa, could language have first evolved here also?

Our knowledge of the origins of speech however, in the throat anatomy of our hominid ancestors. This vital discovery was made by palaeoanthropologist Alan Walker in the course of his study of the skeletal remains of the Nariokotome boy, which have been dated to 1.5 million years BP [Before Present]. This African hominid skeleton, a representative of Homo ergaster [excavated at a site west of Lake Turkana in Kenya in 1984] was so well preserved that Walker felt certain that it held the key to unlocking the secret as to when our ancestors learnt to speak.

A piece of vertebrae with a nerve canal much smaller than a human’s was the clue Walker needed. When modern humans speak, they control how much breath is expelled to make each sound of each word in a sentence. This breath control requires the muscle in the chest wall to develop in a specific way – one that varies depending on the language spoken. Fine control of these muscles is necessary to push the air form the lungs through the larynx. The nerves that control this muscle action come out of the spinal cord. Without enough of these nerves, humans would not be able to breathe and speak at the same time. While studying the vertebrae Alan Walker observed that the canal was too small to contain these nerves.

The size of the canal is a lot closer to that in apes than in humans. Not enough nerves were connected to the muscles to control the breath and sustain a sentence. He realised Nariokotome boy was speechless. Thus Homo erectus was very different from modern humans. When the position of the larynx in modern humans is compared with that [based upon fossil remains] of Homo erectus, it can be seen that while ours is well placed about the middle of the neck, that of Homo erectus was situated about level with the top of the neck and with the base of the loser jaw. Man’s ability to speak is of course a function of both the brain and the vocal apparatus, and while we can clearly articulate words, the vocal apparatus of Homo erectus was such that he would have spoken in a slow and rather ‘clumsy’ fashion.

Nevertheless Homo erectus could speak and this ability would have been achieved by proto-Homo erectus, who as represented by the Narrow Neck Plateau skull, as a race must date back at least to late Pliocene times of 2.5 million years ago. Thus it is quite possible that our ancestors first learnt to speak in Australia before their spread out across the earth. Yet environmental conditions certainly played a major role in human evolution, especially here in Australia; for in order to survive our ancestors had to develop better tools for hunting and skulls that developed along with the evolving brain. Communication was the next step assisted by our evolving anatomy. Thus language evolved with Homo erectus in Australia, and very probably well before he entered Africa, following his spread out across the earth from his Australian homeland.

“The Yowie Mystery - Living Fossils From The Dreamtime".

“The Yowie Mystery - Living Fossils From The Dreamtime". Special Dedication. The Authors dedicate this book to the late Charles Melbourne Ward F.Z.S.; F.R.Z.S. known to his great many friends simply as ‘Mel’. Together with his wife Halley, he operated a natural history museum in the grounds of the Hydro Majestic Hotel at Medlow Bath for many years and also another established at Echo Point, Katoomba. It was ‘Mel’ who first taught me how to collect, record and study natural history specimens, beginning when I was aged 11 years old on holidays with my parents at Katoomba in 1954. Thereafter, every school holidays spent in Katoomba began with a visit to ‘Mel’ at his Medlow Bath Museum to inform him how my fledgling natural science studies were progressing!

As a result and after my parents moved from our Lansvale [western Sydney] home to Katoomba, the Gilroys and Wards became close friends. There was hardly a week which did not see me peddling my pushbike from our North Katoomba home up the Great Western Highway to see ‘Mel’ at his museum for more instruction. Mel Ward possessed a wide knowledge of the culture of the Australian Aborigines and that of the former local Blue Mountains tribes in particular.

He was also a firm believer in the “Hairy Man” and supported my researches in this regard. At my 21st birthday party, held at the Homesdale Function Centre, at Katoomba on Saturday night 8th November 1964, I well recall how my old friend, in front of a large gathering, congratulated me on my researches and the large natural science collection that I was forming and then said: “You’ve done a fantastic job Rex, BUT IT’S ABOUT TIME THAT YOU STARTED MAKING SOME BLOODY MONEY OUT OF IT” in a loud voice that brought the house down!

That following week, together with my father Mr W.F. [Bill] Gilroy, I began a search of local venues, which soon resulted in the acquisition of the lease from the Blue Mountains City Council of the Mt York Tea Rooms, outside Mt Victoria, the rest they as “is history”. Two years late, on October 6th 1966, Mel Ward was dead, having passed away in his sleep. He once said to my father that I was “the Mel Ward of Tomorrow” and I am certain that Mel would be pleased to know that I have indeed followed in his footsteps.

Mel led an adventurous life. The son of Hugh J. Ward, a famous Shakespearean actor of the early 20th century, Mel was encouraged to go on the stage by his father but Mel developed a passion for the natural sciences and his wealthy parents helped him become established. In his lifetime of achievement, Mel became recognised as a world authority on Crustaceans and an anthropologist. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales and was pleased when I too became a member of the Society in 1963. He encouraged me, not long before his death, to take on the Presidency of the Society’s Entomological section, where I served for three years from 1966 to 1969.

That he achieved so many things in the course of his lifetime researches is remarkable, because like this author, he was an amateur with not one university degree to his name! I am certain that my old friend would be delighted at the fact that, together with heather, I am now writing and publishing book on the subjects he loved and on the Yowie in particular. He taught me never to blindly follow the textbook and dare to question dogmas and not be told what to think! I have certainly followed his advice. Knowing Mel Ward as I did I know he would wholeheartedly approve of the scientific approach of this book, therefore “Mel”

This Book is for You!

Rex Gilroy - Australian Yowie Research Centre, Katoomba, NSW.

Monday 25th June 2007I also present sensible advice to any future would-be Yowie investigators. The reader will also be awed at the great many discoveries my wife Heather and I have made in all our years together in the field. I feel privileged to be the founder of Yowie research and to have encouraged other, sensible researchers to follow my example. The search for surviving relict hominids in remote, hidden regions of the world, has been called the “last great search”, and it is both a fascinating and exciting one. Rex Gilroy may be contacted at the Australalian Yowie Research Centre, PO Box 202, Katoomba. NSW 2780. Ph 02 4782 3441 or email New Email Address as of June 2009 randhgilroy44@bigpond.com on or visit our website : http://www.mysteriousaustralia.com/ or http://www.australianyowieresearchcentre.com/ or http://www.rexgilroy.com/

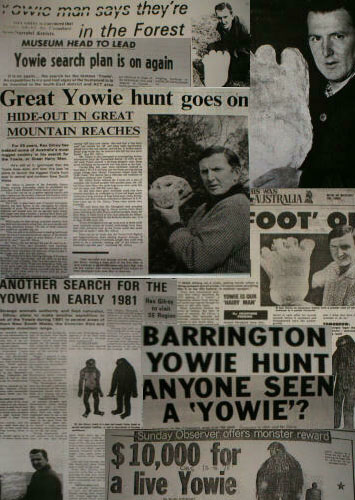

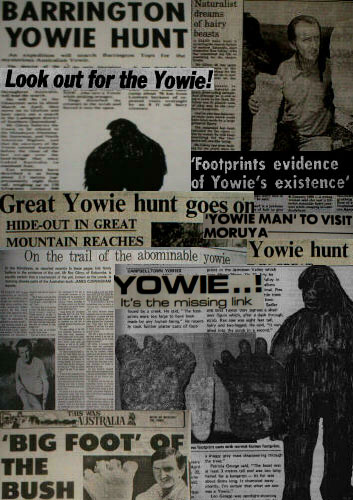

Newspaper Articles on Rex Gilroy's Lifetime Search for the Australian Yowie

Newspaper Articles on Rex Gilroy's Lifetime Search for the Australian Yowie

Aboriginal/Koori Names for the Australian Yowie

To present the Yowie mystery in its proper context, relict hominid evidence from south-east Asia, New Guinea, other west Pacific Islands and New Zealand is revealed, demonstrating how the ancestors of these ‘manimals’ once spread out across the earth via land-bridges that formerly joined Australia/New Guinea/New Zealand with what is now island south-east Asia to the Asian mainland.

“Hairy man” was a name given by the Aborigines to any non-Aboriginal race with which they shared this continent, but the term centred primarily upon at least three basic forms. These forms were either the height of an average human being, an enormous man-like and also ape-like form. All were known by different names Australia-wide, but all meant either “hairy man” or “great hairy man”.