|

Tracking the Cats

Mountain Lions Roam Northeastern Forests, Origins a Mystery

By Wendy Williams

B & W

Photos by Martha Mickles

Courtesy of the Northern Sky News 2002

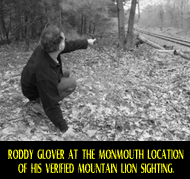

In September 2000, less than 150 miles north of Boston, hunter Roddy Glover was

following a wildlife trail through the woods when a tawny-colored animal caught

his eye. At first he thought it was a deer, but he soon realized it was some

kind of cat. As the cat came closer, Glover saw that it was much too big for a

bobcat, the only wild feline known to roam that area. In September 2000, less than 150 miles north of Boston, hunter Roddy Glover was

following a wildlife trail through the woods when a tawny-colored animal caught

his eye. At first he thought it was a deer, but he soon realized it was some

kind of cat. As the cat came closer, Glover saw that it was much too big for a

bobcat, the only wild feline known to roam that area.

He lay low in the ferns to watch. “Then—it kinda shocked the hell out of me—I

realized it was a mountain lion. And she had a kitten with her.”

Mountain lions were extirpated from New England by early in the last century,

often hunted for the bounty placed on their tails. For decades, sightings of

mountain lions roaming in New England’s north woods have been steeped in

controversy. Those who believe in the presence of mountain lions have often been

considered apt to believe in Bigfoot. Today, most wildlife biologists agree that

there is increasing evidence of mountain lions in the area. But whether or not

the animals —also known as catamounts, pumas, cougars or panthers—are breeding

here remains unclear.

As for Roddy Glover, he wanted proof that he wasn’t crazy. Seeing tracks left by

the female mountain lion in the mud, he called state biologist Keel Kemper, who

arrived at the Monmouth, Maine site within the hour, looked at the tracks, took

photos and made a plaster cast. As for Roddy Glover, he wanted proof that he wasn’t crazy. Seeing tracks left by

the female mountain lion in the mud, he called state biologist Keel Kemper, who

arrived at the Monmouth, Maine site within the hour, looked at the tracks, took

photos and made a plaster cast.

“This is a big cat print,” says Kemper of his plaster cast. “But if I had only

this cat print, I would be foolish to say there was no doubt it was a mountain

lion. I have Roddy Glover, experienced outdoorsman, who watched the cats for at

least five minutes, from only 50 yards away. I’m about as convinced as I could

be.”

A week later at the same location, Glover found another set of what he believed

were mountain lion prints left on railroad ties. This time a biologist who had

done mountain lion research out west came. “Yep,” Glover quotes the biologist as

saying, “those are mountain lion prints.”

In over 60 years, this is the first sighting of a mountain lion roaming free

through New England’s forests that is officially confirmed by accompanying

physical proof (the last was a lion killed in northwest Maine in 1938). But

there have been a number of credible sightings and several other tantalizing

occurrences in recent years. In 1997, near Massachusetts’ Quabbin Reservoir,

wildlife tracker John McCarter found a deposit of large scat covered with debris

in the fashion of a mountain lion. McCarter, and tracker and teacher Paul

Rezendes, sent the scat to a DNA sequencing lab at New York’s Wildlife

Conservation Society. Those tests showed it to be mountain lion scat, a finding

later confirmed by a second qualified DNA testing lab at Virginia Polytechnic

Institute.

Rezendes, author of Tracking and the Art of Seeing, has been following up on

McCarter’s finding: “We’re going to make more of a concerted effort to find

something. Now we’re going to set a track line out this winter... We will be

following up any credible sightings. Anybody who has tracks, scat, anything like

that that sounds credible—if we find something, I’ll be ready to go.”

Massachusetts state biologists accept that the scat was probably mountain lion,

but question the animal’s origins. “One could speculate that a captive cougar

escaped or was released in the area and survived long enough to feed on a beaver

and leave this tangible evidence,” wrote Massachusetts wildlife biologist Susan

Langlois.

Throughout northern Maine, Vermont and New Hampshire, an increasing number of

sightings by very credible and experienced outdoorsmen have been reported. None

of these have been confirmed by physical evidence, however. Some observers have

followed tracks in the snow. In the Brattleboro-Putney area of southern Vermont,

in the winter of 2000, a number of independent sightings were reported over a

series of several days. But to date, nothing has been confirmed.

“We have a semiformal policy of taking all sightings and all calls,” says

Vermont state wildlife biologist Doug Blodgett. “We’re documenting everything we

get, including misidentifications. We’re putting it on a data base and we’re

keeping track.” Blodgett says that when biologists follow up on many of the

calls, the animal turns out to have been a bobcat, a feral house cat, a

coyote—or even a deer.

Because of the similarity in coat color, it’s quite common for the most

experienced people to mistake a deer in a low-crawl for a mountain lion. “I had

that experience myself once,” says Blodgett. “One night I was certain I was

seeing a mountain lion, but when I checked the tracks it was a deer.” Biologists

across the continent tell similar stories of mistaken identities. Because of the similarity in coat color, it’s quite common for the most

experienced people to mistake a deer in a low-crawl for a mountain lion. “I had

that experience myself once,” says Blodgett. “One night I was certain I was

seeing a mountain lion, but when I checked the tracks it was a deer.” Biologists

across the continent tell similar stories of mistaken identities.

Nevertheless, many regional experts agree that, on at least a few occasions,

observers are reporting valid sightings. But, says Blodgett, it is not clear

where the lions are coming from. “We have a lot of people who are quite cranked

up about this, who really want to believe that the lions are here,” he says.

“Some have speculated that there have been some intentional releases. They’re

commercially available— you can buy them on the Internet.”

That the animals could be escaped pets is quite possible. An African lion is

known to be roaming parts of the state of Arkansas, and has been seen on more

than one occasion. (African lions are much bigger that American lions and are

not particularly averse to being seen, so confirmation is a much simpler

process.) In a statewide census, Arkansas biologists have documented several

intentional releases of American mountain lions by owners who no longer wanted

the responsibility of their care.

There may be as many as 100 captive mountain lions in Maine alone, says Kemper.

Just this spring he confiscated three from one person in central Maine who was

keeping six mountain lions, but did not have proper state permits for all of

them.

If, by migration or release, mountain lions were to repopulate parts of New

England, their presence would substantially alter the region’s forests. Before

Europeans came, the cat was the widest ranging and most adaptable of mammals.

Its range stretched from the northern reaches of Canada to the tip of Tierra del

Fuego, and from the heights of the Sierras and the Andes to the swamps of

Florida and what is now Washington D.C.

Because the Florida panther lives in a habitat so different from that favored by

other North American mountain lions, biologists once believed it to be a

separate subspecies, and it is still managed as one. But recent DNA tests show

they have the same genetics—which includes extremely adaptable behavior. Once

thought incapable of surviving too close to human habitation, mountain lions

have recently turned up in basement parking garages on Canada’s Vancouver Island

and seem to do tolerably well drinking swimming pool water in southern

California suburbs.

Myths about the animal’s temperament range to extremes. Some recent magazine

articles have portrayed the mountain lion as a vicious and unpredictable killer

while others describe it as shy and sensitive, more like a feral house cat. The

truth lies in between: the animal has a reclusive temperament, but is also, on

occasion, capable of attacking people. Last winter near Banff, Alberta, a woman

skiing alone through the forest in the middle of the day was killed by a hungry

mountain lion.

Whether New England is big enough to accommodate both humans and mountain lions

is anybody’s guess. No other animal is likely to challenge us in this regard so

much as the mountain lion. Harley Shaw, author of Soul Among Lions and one of

the grand old men of mountain lion research, groans when the subject is brought

up. “We’re growing a human population that’s not tolerant of wildlife,” says

Shaw. “People pay a lot of lip service to wildlife, but when they have to deal

with it in their own backyards, everything changes. Unless we begin to deal with

that, wildlife is destined to disappear from our continent.” Whether New England is big enough to accommodate both humans and mountain lions

is anybody’s guess. No other animal is likely to challenge us in this regard so

much as the mountain lion. Harley Shaw, author of Soul Among Lions and one of

the grand old men of mountain lion research, groans when the subject is brought

up. “We’re growing a human population that’s not tolerant of wildlife,” says

Shaw. “People pay a lot of lip service to wildlife, but when they have to deal

with it in their own backyards, everything changes. Unless we begin to deal with

that, wildlife is destined to disappear from our continent.”

Eventually, as mountain lions migrate into new areas, the nation will have to

determine its true attitude toward this top predator. After all, all

animals—humans included—are wedded to “the daily competition for lebensraum,”

writes Anne Matthews in Wild Nights. “Never in American history have so many

people lived so near so many wild animals; never have our responsibilities as

top predators, ethical and practical, been more unclear.”

Living with wildlife is one thing—living well with wildlife is quite another. In

general, coexistence is an expensive and time-consuming process. It takes time

and energy to develop a management plan to satisfy both human and wildlife

needs. Right now in New England, until a greater amount of hard evidence accrues

pointing toward the presence of mountain lions, wildlife officials are taking a

wait-and-see attitude. State biologists say they won’t be ready to discuss

management policies for the animal until they are convinced a population is

breeding in the region.

But if mountain lions are not breeding here, then where did the kitten Roddy

Glover saw come from? And what is the source of the other mountain lions people

are seeing? Blodgett, the Vermont biologist, puts it this way: “My real

scientific interest is—what’s the origin? Where did that critter come from? To

me, that’s the whole ball of wax.”

Big Cat Footprint Comparison

Wendy Williams, of Mashpee,

Massachusetts, writes frequently about national and international

conservation issues.

What to do if you Meet a Mountain Lion

• When you walk or hike in mountain lion

country; go in groups. A sturdy walking stick is also a good idea; it can be

used to ward off a lion. Make sure children remain close to you and in your

sight at all times.

• Do not approach a lion, especially one that is feeding or with kittens. Most

lions avoid a confrontation. Give them a way to escape.

• Stay calm when you come upon a lion. Talk calmly yet firmly to it. Move

slowly.

• Stop. Back away slowly only if you can do so safely. Running may stimulate a

lion's instinct to chase and attack. Face the lion and stand upright.

• Do All You Can To Appear Larger. Raise your arms. Open your jacket if you're

wearing one. If you have small children with you, protect them by picking them

up so they won't panic and run.

•If the lion behaves aggressively, throw stones, branches or whatever you can

get your hands on without crouching down or turning your back. Wave your arms

slowly and speak firmly. What you want to do is convince the lion you are not

prey and that you may in fact be a danger to the lion.

• Fight Back if a lion attacks you. Lions have been driven away by prey that

fights back. People have fought back with rocks, sticks caps, or jackets, garden

tools and their bare-hands successfully. Remain standing or try to get back up!

Consider yourself lucky if you do get to see a mountain lion during your Bigfoot

expeditions. Many of the old-timers still haven't even seen one.

The photos appear here under the fair use

for educational purposes of copyright material.

|